How Elliptic Curve Cryptography Works

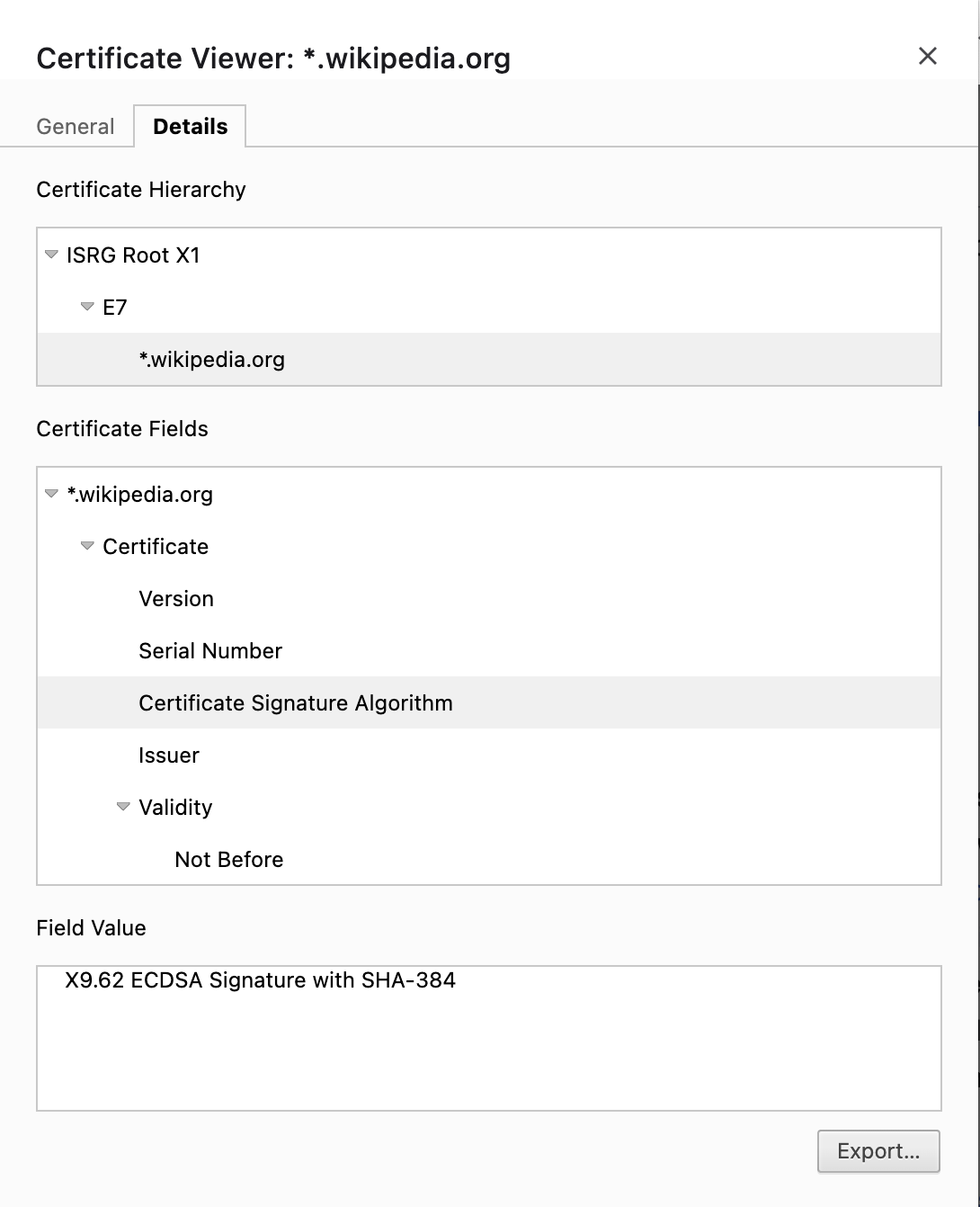

I remember learning about RSA and Diffie-Hellman back when I was doing my computer science degree. But Elliptic Curve Cryptography is very common these days. For example, the signature algorithm on the HTTPS certificate of wikipedia.org uses ECDSA, which stands for “Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm”.

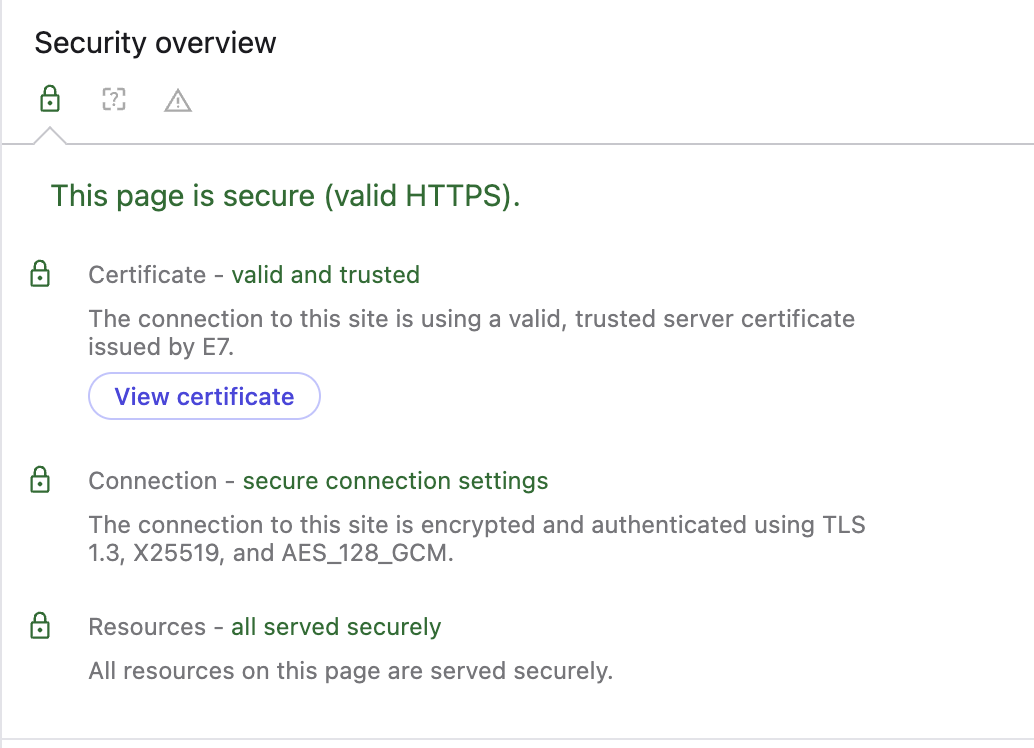

When I look at the connection security info using browser tools, I see that it is using X25519, which is a protocol based on Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman (ECDH):

As another example, when I use ssh-keygen to generate a new SSH key, the default key type is ed25519, another algorithm based on elliptic curve cryptography.

% ssh-keygen -f tmp.key

Generating public/private ed25519 key pair.

Enter passphrase for "tmp.key" (empty for no passphrase):

So how does this all work? Let’s find out.

Why use ECC?

Before we dive in, let’s talk about why. Why would we want to use something like ECC instead of the venerable RSA?

The main reason appears to be key size. A 256-bit ECC public key provides comparable security to a 3072-bit RSA public key. This is almost a 92% reduction in the size of the keys that would need to be stored, transferred, and used.

Another interesting side benefit is that ECC algorithms tend to be more complex to understand and implement, and the security issues are more nuanced and subtle. This means that developers are less likely to try to “roll their own” ECC algorithms, and more likely to use battle-tested implementations instead, reducing the chances of making implementation mistakes.

What is ECC used for?

The interesting thing is that, in general, Elliptic Curve Cryptography isn’t actually used directly for encrypting data. It can be, but for the most part it is used for digital signatures, and key agreement (using Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman, or ECDH). Once a key is agreed upon, a cipher such as AES-GCM may be used for encrypting data.

Ok, so how does it work?

For this explanation, I’m going to assume you already understand RSA at a basic level, meaning that you understand how modular arithmetic works.

ECC is a type of public-key cryptography. In general, public-key crypto requires an “intractable” mathematical problem, which is a problem that is theoretically solvable, but takes an impractical amount of time and/or resources. In the case of RSA, the intractable problem is factoring the product of two large primes that are not close together (\(N = pq\)). For the standard Diffie-Hellman key exchange, the intractable problem is the “discrete logarithm” problem. In other words, given a publicly known prime modulus \(p\) and base \(g\), if we know the number \(A\) where \(A = g^a \mod p\), we cannot efficiently find \(a\) if \(p\) and \(g\) are large (e.g. 2048 bits in length).

For ECC, the intractable problem is very similar to the discrete logarithm problem for Diffie-Hellman, in fact it is even called the “Elliptic Curve Discrete Logarithm Problem” (ECDLP). But before we get into what that actually is, we need to cover some background in what elliptic curves are, and how to perform operations on points within the curves.

Elliptic Curve Equations and Points

There are various types of elliptic curves. For the purpose of this post, we are going to talk about curves arising from the so-called “Weierstrass equation”. Given parameters \(a\) and \(b\) (with some restrictions on their values), the equation takes the form:

\[y^2 = x^3 + ax + b\]Some examples may look like the following:

Note that because of the \(y^2\) term on the left, the curves are always symmetrical above and below the \(x\) axis.

A point on the curve is any \((x,y)\) pair which satisfies the equation. Capital letters are typically used to denote points, for example \(P = (x_0,y_0)\)

In ECC, we also have an additional constraint. Rather than using continuous curves, we limit our operations to integers mod some large prime \(p\). This will come into play later, but for the sake of visualization, it’s easier to think of the curves as being continuous for now.

Operations on Points

Next, we can define some operations. Specifically:

- Addition of two points: \(P + Q\)

- Negation of a point: \(-P\)

- Multiplication of a point by a scalar: \(nP = P + P + P + …\) (\(n\) times)

This is where things get a little weird, so hang in there.

First, negating a point simply involves negating its \(y\) coordinate. So if \(P = (x_P,y_P)\) then \(-P = (x_P,-y_P)\). Visually, negating a point involves finding the other point on the curve with the same \(x\) coordinate, mirrored across the \(x\) axis. In the diagram below, in pane 3, \(P = -Q\).

Next, we define a “special” point \(O\). This point is stated to be “at infinity”, and is defined as the identity of the addition operation. This means that \(P + O = O + P = P\) and \(P + -P = O\). It behaves like the number \(0\) in regular addition.

Point addition is strange. It is defined based on the “roots” of a line intersecting the curve. For any given line, there will be one, two, or three points where it intersects the curve. If there are three such points \(P\), \(Q\), and \(R\) (see pane 1 below), then addition is defined such that \(P + Q + R = O\). So if we want to compute \(P + Q\), we draw a line that goes through those two points, find the third point \(R\) which also intersects with that line, and define the result as \(-R\) (the point on the opposite side of the \(x\) axis).

Now, what if we want to add a point to itself? In that case, we draw the tangent line at that point, and do the same operation. In pane 2 below, we compute \(Q + Q\) and see that it is \(-P\).

Finally, as a special case, if \(P\) is a point with a vertical tangent line (pane 4) then \(P + P = O\).

If you’re confused (I certainly was) this site has some great visualizations that helps to understand how point addition works, and scalar multiplications.

The reason to define addition in this way is because it has some nice mathematical properties. It is associative

\[(P + Q) + R = P + (Q + R)\]And commutative:

\[P + Q = Q + P\]Because of this, and the fact that it has an identity (\(O\)) and an inverse operation (\(-P\)), the operation forms an “abelian group”, which makes it behave “nicely” in a mathematical sense.

Now, luckily, when we want to add points together, we don’t actually have to draw any lines at all! Some smart mathematicians have figured out handy little formulas for adding two distinct points, and for adding a point to itself (also known as “point doubling”). These formulas are different depending on the type of elliptic curve, but for Weierstrass curves, they are as follows.

To add points \(P = (x_P,y_P)\) and \(Q = (x_Q,y_Q)\) and get point \(R = P + Q\), we first compute \(\lambda\):

\[\lambda = {y_Q - y_P \over x_Q - x_P}\]And then we determine the coordinates of \(R\) as follows:

\[x_R = \lambda^2 - x_P - x_Q\] \[y_R = \lambda(x_P - x_R) - y_P\]Similarly, to compute \(P + P\) (i.e. \(2P\)), we compute \(\lambda\) as follows:

\[\lambda = {3x_P^2 + a \over 2y_P}\]And then we compute \(x_R\) and \(y_R\) as above.

Point Multiplication by a Scalar

From the above, we can see that point multiplication \(nP\) is simply the operation of adding the point \(P\) to itself \(n\) times. However, this is not a very efficient way to do it. There are several algorithms for point multiplication, some of which depend on the type of curve being used. But the simplest and most generic way is using the double-and-add algorithm, which requires \(\log_2(n)\) iterations to complete. You can read more about how the algorithm works here.

Elliptic Curve Discrete Logarithm Problem (ECDLP)

Ok, this is where things start getting useful. As mentioned above, for cryptographic purposes, we restrict our definition of points to those with coordinates that are integers mod \(p\). All of the above definitions and formulas still work, although note that since we’re working with integers mod \(p\), all division operations above must be done by multiplying by the multiplicative inverse mod \(p\).

Now, finally, the ECDLP. If we are given a point \(G\) on an elliptic curve, and a second point \(P = nG\), but we do not know the value of \(n\), finding its value given only \(G\) and \(P\) is an intractable problem. This is the ECDLP.

In other words, given \(G\) and \(P\), we know that \(P\) was determined by adding \(G\) to itself some number of times \(n\). But there is no better way to determine \(n\) than to simply try every possible value until we get \(P\).

There are, however, a lot of weird special cases that make the ECDLP easier to solve. Basically, you need to have good curve parameters \(a\) and \(b\) and a good “generator point” \(G\) in order for the problem to be hard, and the cryptographic operations to be secure. There are standard ECC curves and parameters that are known to be secure. Just use those.

Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman (ECDH)

When we want to encrypt some data between two recipients, for example a web server and browser, we might use Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman to establish a shared secret key, and then use some other cipher to encrypt the communications (e.g. AES-GCM). With ECC, the Diffie-Hellman algorithm is quite simple.

Alice and Bob both begin by agreeing on curve parameters (e.g. they choose the NIST standard P256 curve and generator point). This will include a number \(n\) which is the “order” of the generator point \(G\), defined such that \(n \cdot G = O\) (for standard, secure curves, \(n\) is also a large prime number). Now, each party chooses a private key \(d\) by choosing a random number in the range \([1, n-1]\). Then, they each compute a public key \(Q = d \cdot G\). So then Alice will have \((d_A, Q_A)\) and Bob will have \((d_B, Q_B)\).

Now Alice and Bob share their public keys \(Q_A\) and \(Q_B\). This may be over an insecure communication channel, and because of the ECDLP, an eavesdropper cannot determine \(d_A\) or \(d_B\), despite knowing \(G\), \(Q_A\), and \(Q_B\).

Finally, Alice and Bob compute a shared secret key \(S\) as follows:

Alice computes \(S = d_A \cdot Q_B = d_A \cdot d_B \cdot G\)

Bob computes \(S = d_B \cdot Q_A = d_A \cdot d_B \cdot G\)

They then each use the \(x\) coordinate of \(S\) as their shared secret. This may be used with any symmetric key encryption algorithm.

Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA)

Finally, let’s talk about the ECDSA, which is used for signing digital data such as TLS certificates. This is a little bit more involved, but it follows the same principles.

If Alice wants to send a signed message to Bob, first, as usual, they must agree on the curve parameters. This includes \(a\), \(b\), generator point \(G\), and the order of the generator point \(n\).

Then, Alice generates a private key in the same way as above (a random number in the range \([1, n-1]\)). She then computes her public key \(Q_A = d_A \cdot G\).

Then, Alice generates a signature for a message \(m\) by following these steps:

- Calculate \(e = \text{HASH}(m)\) using a cryptographic hash function such as

SHA-2. - Compute \(z\) as the leftmost bits of \(e\) such that \(z\) has the same bit length as \(n\).

- Generate a unique, cryptographically secure random integer \(k\) from \([1, n-1]\).

- Calculate the point \((x_1,y_1) = k \cdot G\).

- Calculate \(r = x_1 \mod n\). If \(r = 0\) go back to step 3 and repeat.

- Calculate \(s = k^{-1}(z + rd_A) \mod n\). If \(s = 0\) go back to step 3 and repeat.

- The signature is the pair \((r, s)\).

Then, the message \(m\), the public key \(Q_A\), and the signature \((r, s)\) is sent to Bob. Bob may validate the signature as follows:

- Validate \(Q_A\) by checking that it is not \(O\), it lies on the curve, and \(n \cdot Q_A = O\).

- Verify that \(r\) and \(s\) are integers in \([1, n-1]\).

- Calculate \(e\) and \(z\) as above.

- Calculate \(u_1 = zs^{-1} \mod n\) and \(u_2 = rs^{-1} \mod n\).

- Calculate the curve point \((x_1, y_1) = u_1 \cdot G + u_2 \cdot Q_A\). Ensure \((x_1, y_1) \ne O\).

- The signature if valid if \(r = x_1 \mod n\), otherwise it is invalid.

This works because:

\[(x_1, y_1) = u_1 \cdot G + u_2 \cdot Q_A\] \[= u_1 \cdot G + u_2 \cdot d_A \cdot G\] \[= (u_1 + u_2 \cdot d_A) \cdot G\]Now we plug in the definitions of \(u_1\) and \(u_2\) from the validation algorithm (step 4):

\[= (z \cdot s^{-1} + r \cdot d_A \cdot s^{-1}) \cdot G\] \[= (z + r \cdot d_A) \cdot s^{-1} \cdot G\]And then we expand the definition of \(s\) from the signature algorithm (step 6):

\[= (z + r \cdot d_A) \cdot (k^{-1} \cdot (z + r \cdot d_A))^{-1} \cdot G\] \[= (z + r \cdot d_A) \cdot (k^{-1})^{-1} \cdot (z + r \cdot d_A)^{-1} \cdot G\] \[= k \cdot G\]So the \(r\) that we compute in the validation algorithm must be the same \(r\) that was originally computed in the signature algorithm. If they differ, the signature is invalid.

Conclusion

There is much more to ECC, but this should serve as a good primer to understand the basics of how it works under the hood. I may write a follow-up post down the road to describe some of the issues that have cropped up with ECC over the years. As with many crypto algorithms, seemingly insignificant issues with the implementation can often completely break the security of the entire algorithm. As always, it’s important to use mature and tested implementations of the algorithms to avoid such issues.

But for now, hopefully that was a helpful overview!